Music for Sunday

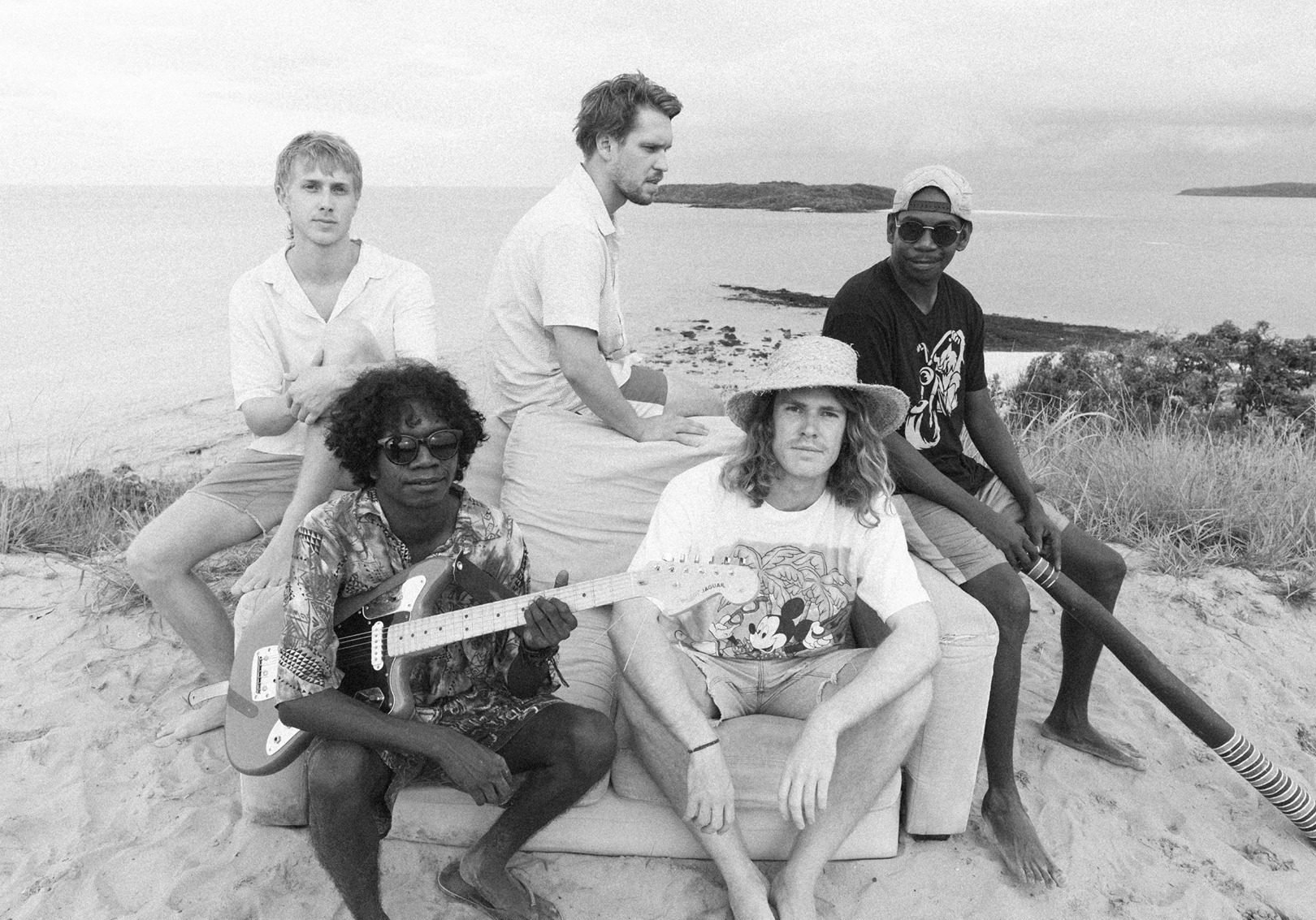

/You could start the morning with King Stingray, the band that won last year’s ARIA for breakthrough artist, as they are probably the most recent in the line, or don’t even worry about the line, just listen to their debut, self-titled album for what the band members call Yolngu surf rock, its energy and exuberance of happy people by a happy sea enough to soothe a soul in need of soothing. You won’t be able to help but sing along to ‘Get me Out’ (of the city). ‘There’s a place where you live and a place where you grow,’ Yirrnga Yunupingu assures us. Songs about long highways and loving life and home, the line you are exploring could be music from Arnhem Land, where music has been made for at least sixty thousand years.

You could move from King Stingray to Gurrumul, particularly if you have reason for tears. You might start with ‘Bayini’, from the second album Rrakala, perhaps the version with Delta Goodrem. ‘It’s all about life,’ she starts on her own after the first refrain, ‘and love for the land,’ giving us a lesson in what Gurrumul’s music is teaching, before they sing together, in one of his Yolngu languages, her passionate low register with his soaring melody. If that doesn’t bring tears, nothing will.

While we’re on the tears, you could watch the documentary about Gurrumul’s life. He rarely sang in English or spoke on stage and even in the documentary, he’s not interviewed; director Paul Damien Williams is a fly on the wall in important moments: here, the singer, blind since birth, on a tour bus, tilting his head and listening to the world around him; here, in a hotel room, laughing with friend and musical collaborator Michael Hohnen, who’s shaving him; and here, in another hotel room, a telephone on a side table, on the line to family back on Elcho Island, so they can hear him and he can hear them.

The wry humour shines. When Gurrumul is working out how to make sense of Sting’s song ‘Every Breath You Take’—which he is to perform in just a few hours with Sting himself at Sting’s personal request—calls are going back and forth to Elcho Island to try to find a way through so the song sits right for Gurrumul’s family and culture. At one stage, time getting on and his team increasingly worried it won’t come together, Gurrumul walks into the room, singing, ‘Every breath you take, I’ll be watching you, except I can’t because I’m blind.’ The final performance is just all Gurrumul, transcended by his calm presence, and that voice. Sting comes to the dressing room afterwards to thank the singer and I mean no disrespect to Sting except to say he is irrelevant and looks as if he knows it.

You would do well to stay a while with Gurrumul, because while his passing at the age of just forty-six in 2017 was a tragedy for the entire world, his music, his gift to that world, is still with you. If you end the session with his last album, Djarimirri, Child of the Rainbow, you might find some anger but also soaring joy. He spoke hope for a world, even a hopeless world.

You might finish the Sunday music with the eighties band Gurrumul played in and King Stingray hail from, Yothu Yindi, whose foundation members Dr M Yunupingu and Stuart Kellaway are family to King Stingray members Yirrnga Yunupingu and Roy Kellaway. The song ‘Treaty’ was a number one hit in 1991 when your generation was twenty or thirty-something. You had no clue then. You still don’t.

You removed yourself for the last week to a cottage made of stone and wood in Warrabah national park, warrabah the name of a local turtle, and the cottage, Muluerindie, the name of a local river. On the way, you stopped in Glen Innes where outside the polling place, you happened upon a band of four women with t-shirts matching yours. An older fellow asked them where the no supporters were. They should be here, he said. You’re dividing the country, he added. The yes crew, Anna, Margie, Margaret and Rose, tried to engage him, curious, polite, kind. He wasn’t interested and soon left. What courage they had, you think afterwards, courage you wish you had too.

In the week away, you have seen a superb fairy wren, and every morning when the sun is just right to make the big windows overlooking the river reflective, the tiny bird throws itself against the glass with all its might, its beak making a rat-a-tat against the pane. You wish it would stop, as it looks as if it will hurt itself. Perhaps one day, it will break the glass. You also see the critically endangered regents honeyeater, which you don’t realise is important until it flies off, and a wedgetail eagle, perched in a tree. Yothu Yindi is a Yolngu matha term meaning child and mother. You have thought of your daughter often, the one you gave to strangers, as the grief and longing of a country have ebbed and flowed.

The song ‘Gurrumul History’ from Gurrumul’s first self-titled album is one of the few songs that’s partly in English. ‘I was born blind,’ he sings, ‘and I don’t know why. God knows why, because he love me so. How can I walk, straight and tall? In any society, please hold my hand.’

Vale.